CLOCKS FOR SEEING: THE OTHER

Why do photographs-- still images-- survive? In this media saturated culture where video is king there remains a vital place in our lives for frozen moments in time-- simple still photographs, produced by what French critic Roland Barthes called “clocks for seeing,” his crazy/perfect description of a camera. For me it seems to be the collision between the profound, deep seated human need to find meaning-- not just in our lives but the meaning of life itself-- and the way our brains must decode still photographs.

There must be some evolutionary twist in our brain development that causes us to be immensely attracted to and compelled to pause and study photographs, even images we are not particularly interested in. When I think hard about memory and my past, every memory is conveyed in a frozen still image in my mind. There is no film running, no motion. Each event is summed up in a moment. And then a series of cascading moments follow, but these are individual frames. I think this is true of most people. Our brain patches these together exactly like frames in a film so we get the impression sometimes our memory is flowing like a film. I don’t think it is a film.

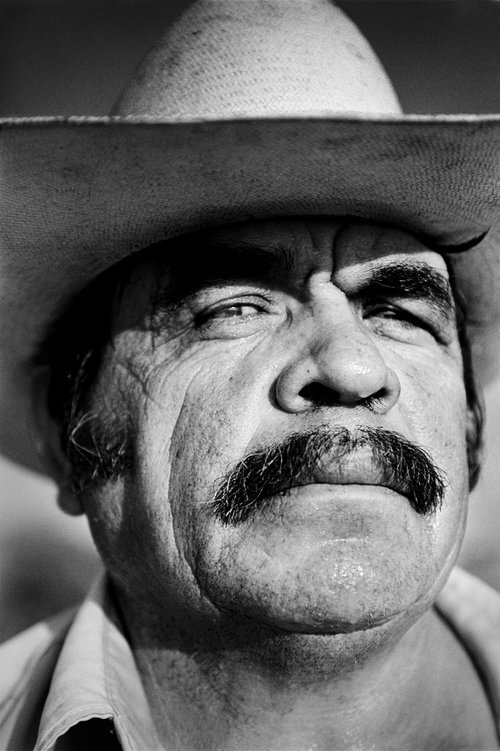

We look at photographs to find ourselves, our place in the world. We learn and affirm who we are and our place in our culture by identifying with the subjects or by opposition and by our differences with the subjects. This ties into the meaning of the “other” and the connections we make with strangers we encounter. We are all human but what is their experience? We wonder and are fascinated by strangers in strange cultures, their clothes, habits, beliefs. This curiosity is particularly well served by the still image precisely because it is fixed, still, frozen and available for long study.

Now I understand that I photograph with an unconscious purpose other than to simply document a people or place I am interested in. Like everyone else, I need to find my place in the world and understand who I am. This is not something I think about, it’s part of human DNA and so I’m constantly attracted to the “other” and looking to connect. It's meeting a stranger as you press the shutter.

Recently I came across the famous Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski’s fantastic book “The Other” which deals at length in an extremely accessible way with this subject. In the introduction there is a reference to the French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas’ wonderful quote that sums it all up: “The self is only possible through the recognition of the Other.” Exactly.

As I’m pondering the “other” and why photographs have survived all the changes in our culture and technology, I’m thinking of my friend and mentor Dennis Stock and his opinions about exactly what qualities a photograph must have to succeed and last the test of time. Dennis believes photographs that have certain qualities explain why the still image has remained useful and part of the culture. Over dinner at our house in Woodstock, I began to describe a recent show of contemporary photography I’d seen that was entirely conceptual, as opposed to overtly emotional. It was purely an intellectual exercise and you could read the artist’s statement and agree or not, get the point, perhaps appreciate a little better the imagery, but it was art. Subjective and debatable as to its merits.

Dennis is never shy of his opinions and began a critique of contemporary fine art photography. I lamely interjected that rules are made to be broken. “Bullshit,” he cried, slamming his hand on the table. “Do you want your pictures to be memorable or not? Be serious!”

His point was that most contemporary work was going to pass by in a flash and disappear. To be useful it has to be memorable. To be memorable it has to follow certain fundamental principals passed down through Aristotle’s golden mean. He reminded me of Cartier-Bresson’s comments, roughly paraphrased here, that it is not enough to capture the moment, the photographer must at the same time position the subject in a compelling geometric composition. He suggested I go back and look at all my favorite images from the 20th century and promised I would see HCB’s ideas were correct.

I have to report that I did look up the golden mean again and copied one out. I pulled out many of my old photography books of my heroes and inspirations and damn if almost all of the images I’d remembered seeing in my youth did in fact fit with Dennis' beliefs and combined a moment with classic geometric composition.

Does it then follow that what Aristotle discovered about composition is related to how our brains evolved to perceive still images? And therefore, to take photographs that will become important to the culture, that we always remember, must by default always follow a set of compositional rules?